Despite numerous advances in healthcare financial analytics, cost accounting continues to get tripped up by the same old issues. If you've been in the field for more than 10 years, you know what I mean. I attended the annual user group conference for a leading decision support system vendor a few years ago. During the costing sessions, it struck me how today's challenges faced by cost accountants are the same challenges we grappled with back in the early 1990s.

Introduction

Yes, we have made groundbreaking progress with our event-based costing methodology which leverages data one can glean from the patient care systems. But these efforts can also be held hostage by garbage data in the source systems, inadequate resources to acquire the data, or lack of a sophisticated platform to ingest, report, and analyze the patient cost data.

Frequently, the lack of accurate costing data is easily traced back to strategic and tactical missteps by the custodians of the source data: ERP (General Accounting/Supply Chain/HR) and Revenue Cycle Management are prime examples. If your organization is contemplating or initiating a new ERP platform and Cost Accounting does not have seat at the table, you will be underwhelmed with the final product as it relates to your costing data needs. Maybe this is a topic for another blog.

Supply Acquisition Cost: The Wild West?

Good progress has been made in the past 15-20 years determining the true cost of patient care supplies, but it has been limited to what has been documented in the surgical logs. Granted, that is a huge expense, but supply cost accuracy can fall short in a few key aspects. Specifically, intraoperative systems such as Epic OpTime and Cerner SurgiNet have the capability to capture actual cost of supplies (billable and non-billable) consumed on each patient case. This currently is the gold standard in reporting supply costs, but not without due diligence:

- Audit the compliance of intraoperative staff in recording the usage of supplies during each case. Is it barcoding or manual typing? Is everything used getting captured?

- Audit the accuracy and robustness of the interfaces between your supply chain system and the intraoperative system. Are the costs for stock items coming across in near real-time and are they correct?

- Understand which clinical areas utilize intraoperative logging and which do not. Specifically, high-cost areas such as Cath Lab, Electrophysiology, and Interventional Radiology frequently have their own systems which may or may not be easy to integrate into costing.

- Make an effort to capture wasted supplies, especially implants. Ensure you can record these in your costing database.

If you find deficiencies in any of the above, especially items 1 through 3, you need to develop a remediation or contingency plan. The remaining portion of this newsletter will deal with the most common alternative for billable supply costing: "backing into" the cost by inverting the charge markup.

Supply Cost Markup Formula

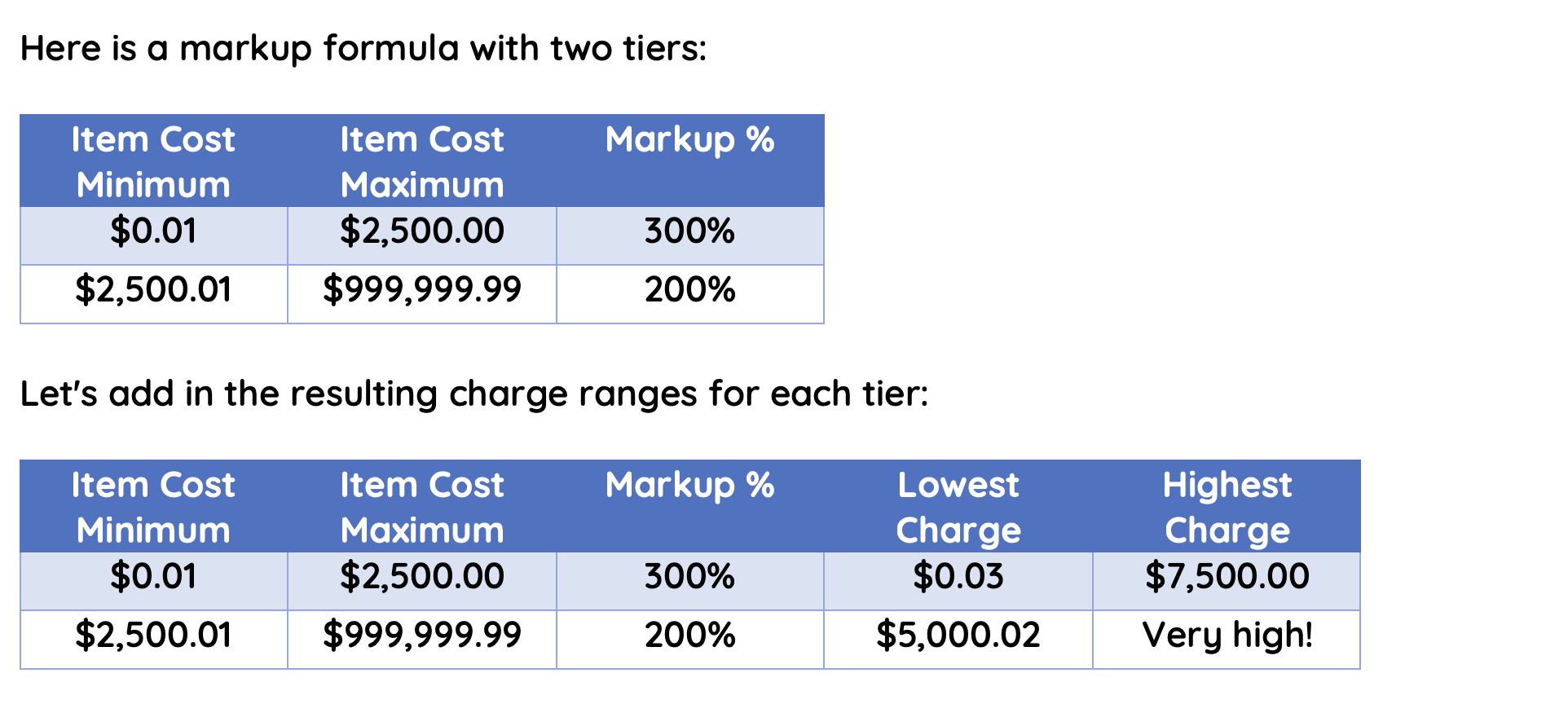

Every US hospital has a formula to determine a gross charge based on a supply item cost. Yes, in most cases, charges don't matter, but for the Cost Accountant, charges are important. The markups are segmented into two or more tiers based on cost ranges for the supply item. As the cost of the item increases, the markup usually decreases. I've never understood the logic behind a progressively decreasing markup: is that to make the charge somehow more palatable for high-cost items?

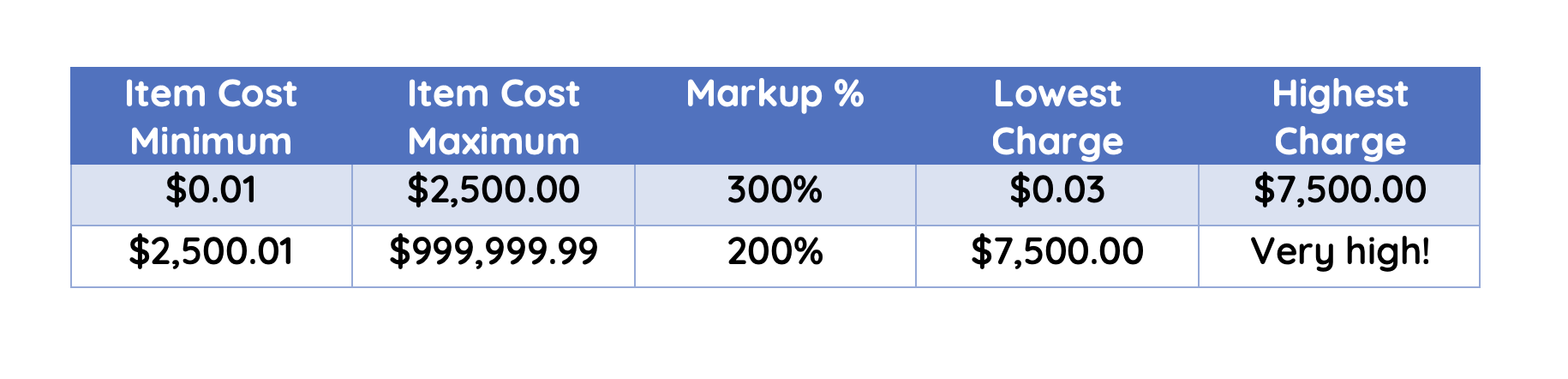

However, these markups have a hidden surprise which makes life difficult for the cost accountant, and also results in nonsensical charge amounts at the tier breakpoints. Here are some simple examples.

Looking at the above table from a charging perspective, a serious issue might be hidden. Assume you have two different items, one purchased for $2,500 and the other purchased for $2,600. If you plug each of those costs into the formula above, the item costing $2,500 will have a charge of $7,500 because it falls into the 300% markup. The item costing $2,600 ($100 more than the first item) will have a charge of $5,200 (200% markup). In other words, the charge for the higher cost item is actually less than the charge of the less expensive item. Has anyone noticed that?

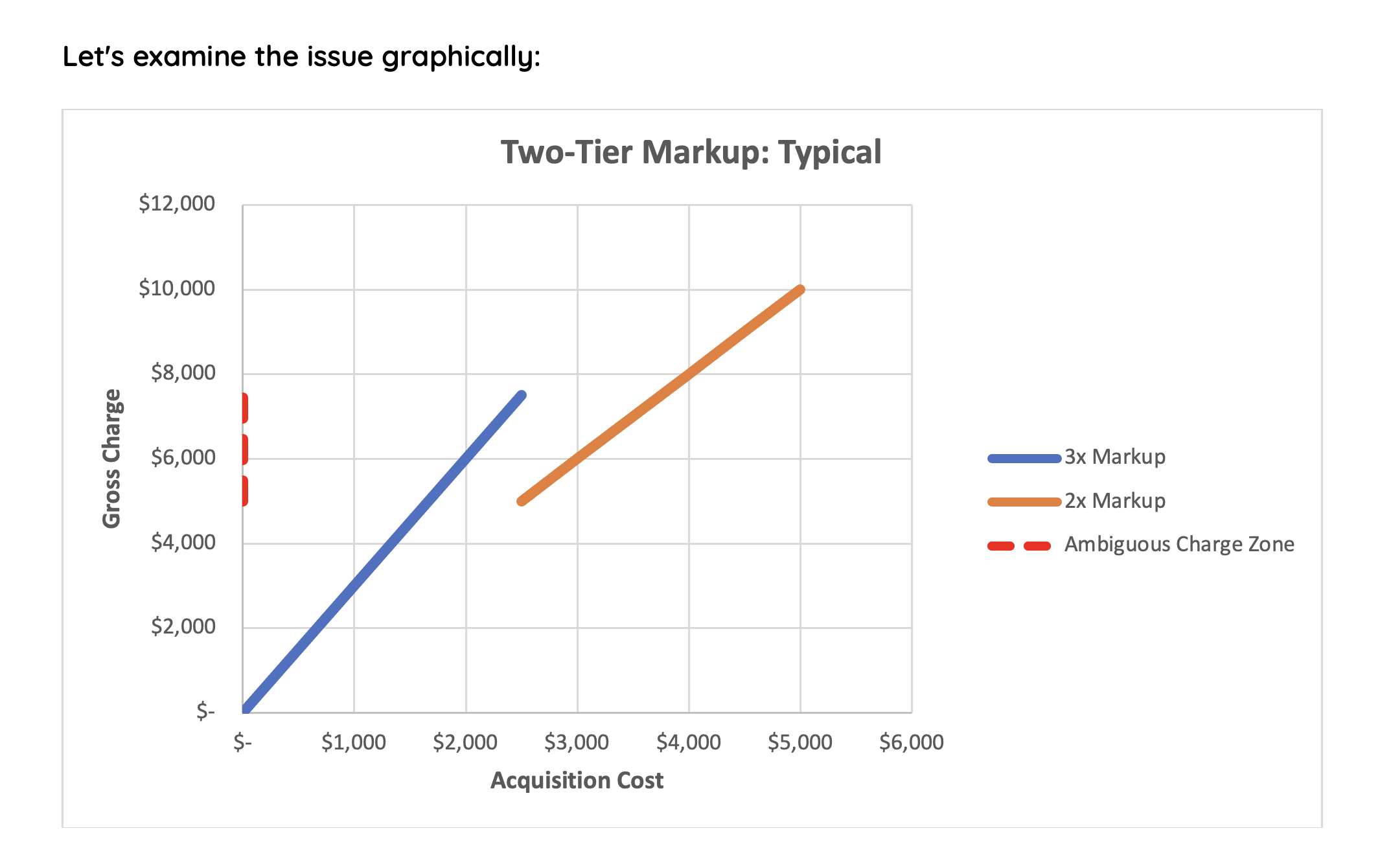

As you increase acquisition cost and reach the tier break point ($2,500), your resulting charge immediately decreases because of the lower markup of the next tier. If the cost accountant attempts to reverse engineer the charge markup to derive the item cost, they will face a dilemma in what I've labeled the "Ambiguous Charge Zone ": the lowest possible charge in the higher tier through the highest possible charge in the lower tier. In this zone (charges of $5,000.02 through $7,500.00), the markup multiplier could be either 200% or 300%. Which is it?

Assume you have a cardiac stent billed to the patient at $6,000 and you need to talk to your cardiologists about stent utilization vs. cost. Did that stent cost your facility $3,000 (200% markup) or $2,000 (300% markup)? This might be important to know before you have that discussion. You might think the answer will be found by looking at the charge description (DES STENT LEVEL II) and matching to the Cath Lab purchase orders, only to realize that charge description is much too vague to be of any help.

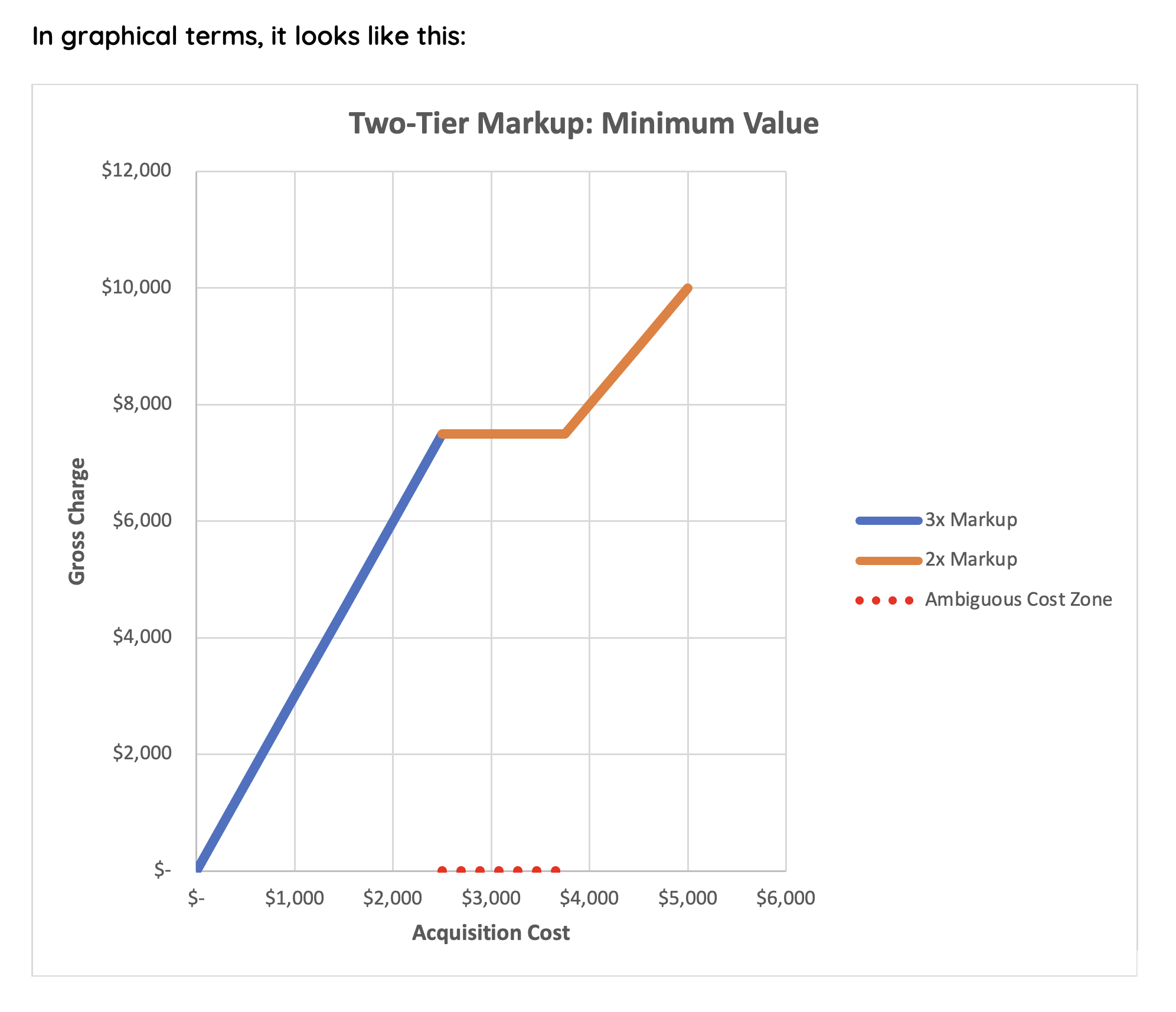

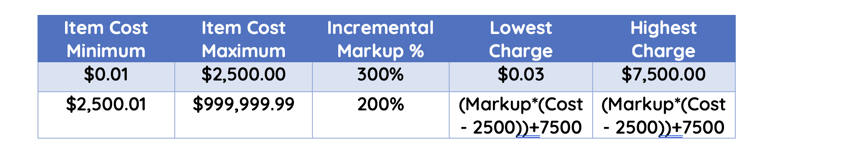

Let's look at two possible solutions to ambiguous markups, neither of which I've seen any hospital actually implement. Is it because the math is too hard? No, it's the typical "We've always done it this way." Or it's "Charges don't matter," except when they do. The first example is a step function markup preventing the calculated charge at the tier breakpoint from being less than the maximum of the lower tier.

While this solves the problem of never charging less for a higher cost item, it still is a problem for the cost accountant seeking to derive cost from the charge. We have a range of costs (the Ambiguous Cost Zone) from $2,500 to $3,750 which will have the same $7,500 charge. For all charges which are not $7,500, the reverse markup formula may work reliably.

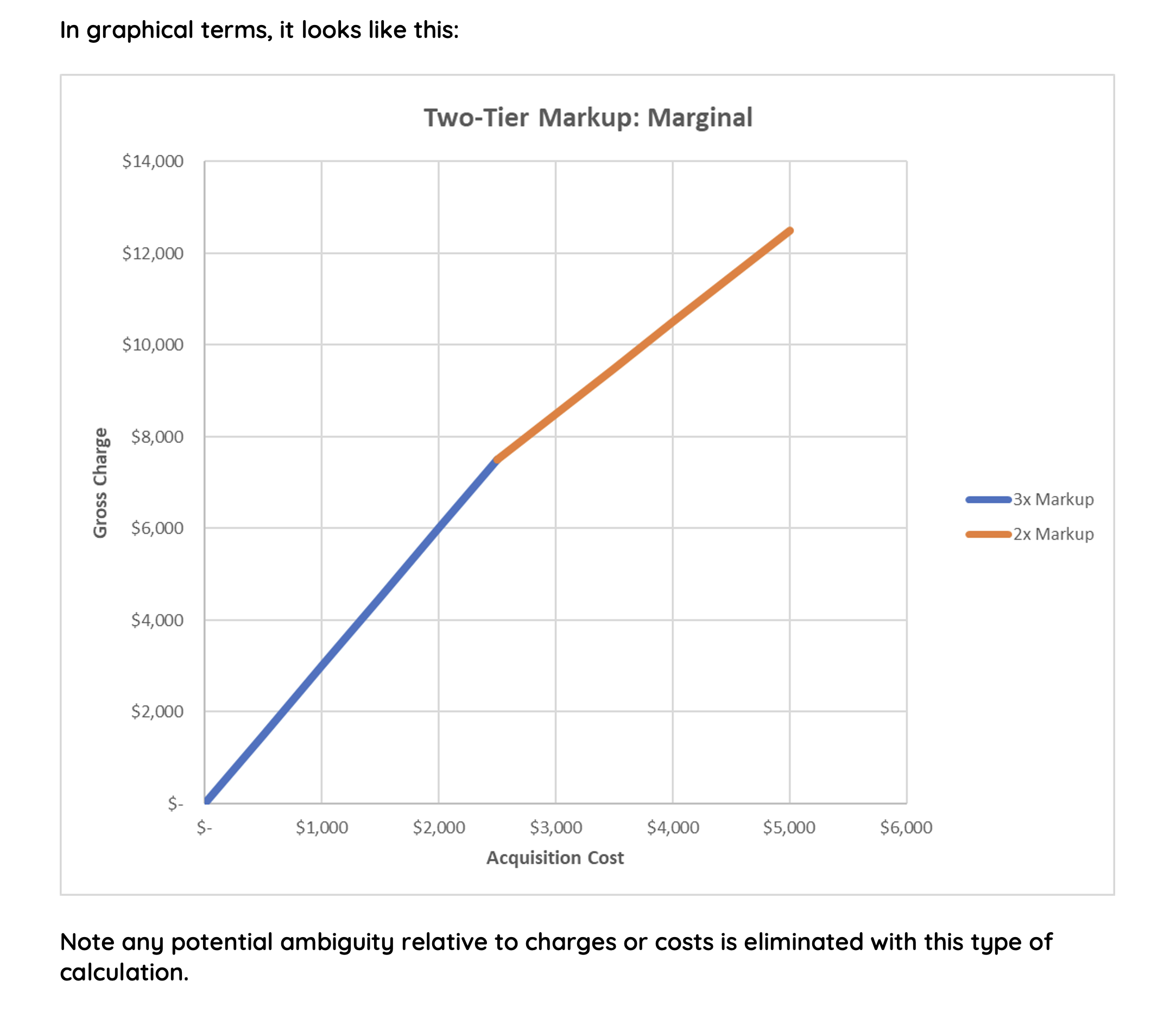

By far the best approach to designing a fool-proof markup schedule is to use a marginal increase method, conceptually like federal tax brackets. This process ensures every incremental increase in item expense results in an incremental increase in gross charge, and it can be modeled in reverse to derive cost from charge.

More Pitfalls Await

Assuming the cost accountant navigates the landmines mentioned above, there is one other major fallacy in their way, especially for "stock" items (items on hand in inventory or on the item master). I'll walk you through the typical life cycle of a billable stock supply item:

- Item is added to supply chain item master.

- Item is added to charge master and the charge is determined using markup schedule.

- Item charge is increased during the annual charge (price) increase.

- Repeat step 3 every year.

Can you see what is wrong with this process? Once the item is in the domain of revenue cycle, the charge is increased annually with no respect to the item's current cost. The relationship between item cost and item charge has been decoupled. If your charge increases are not at the same rate of cost increases of your item, the now current markup schedule with respect to that item is null and void. The longer the item has been in inventory or in the item master, the further out of alignment with your markup schedule it will be. I've seen effective markups of 1000% or more because of compounding revenue increases. The cost accountant will never be able to "back into" the item cost with any degree of accuracy.

Conclusion: Understand Your Data

I know I've painted a bleak picture, and there's very little a cost accountant can do to mitigate these issues in the short term, except this: assess and understand the quality of your data. Know which data elements are reliable and which are not. If your cardiac supply cost data is built by backing out charge markups, then be certain to share the data with many caveats and disclaimers. Longer term, educate your Accounting, Finance, Supply Chain and Revenue Cycle leaders on the fundamentals of cost accounting (aka "managerial accounting"). Impress upon them that you are the "tail of dog". And wrangle your way onto the next ERP upgrade steering committee!